The Electronique Void Instrumentals (LP)

This, too, is a story about control. It’s a manual, maybe half Rosetta Stone, half bird guide. It was made the way they made electronic music in the good old days, all analog everything, right after synthesizers shrunk to a manageable size and you didn’t have to trek down to a university to use one anymore. Hard-earned. Tastes different. Our parents’ electronic. And its subject is staying together, that thing we thought was their province. It’s about trying to fix what hurts. It’s about knowing better. Black Noise is men talking to men about women; Lemonade is a woman talking to women about men, and they both orbit around a failure we take for granted like the sun: loving you is complicated. It’s a skill; we forgot.

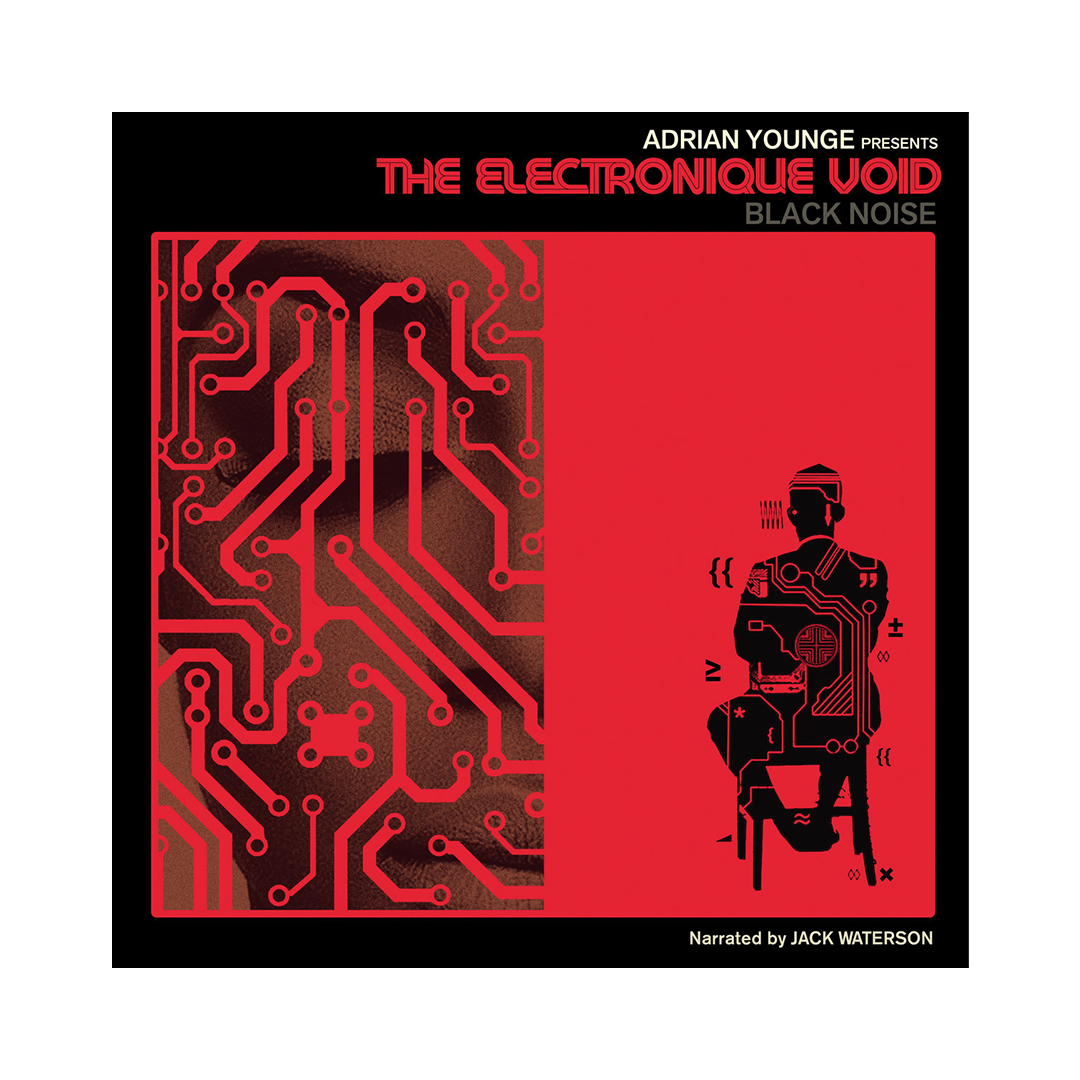

Adrian Younge calls The Electronique Void an academic album, by which he means it is both instructional and informational. There’s a problem at the heart of it, a woman who’s been told that she’s loved, but she doesn’t recognize that, can’t feel it, may have heard it all before, may be worrying about the wrong things. Jack Waterson, long a guitarist in Younge’s band, plays the role of narrator, sounding professorial and rather superior as he lays out for the woman where she’s erred. That vocoder you hear is Adrian, talking to her on a subterranean level, the way an artist must. There’s a strong sense of rules here, a prescription and a presumption that there is an agreed upon way to do it, and there is also a wrong way, or at least a way that won’t work. And the fact is, as didactic as that sounds, it might be the truth. Maybe everybody who’s alone can be cured. The discourse on the album is the kind of thing that happens when you go blonde and then you can’t keep ‘em off you. These truths are cold and hard, and our hero begrudges the well-meaning advice being rained down upon her as any independent woman would.

The science of love, its formulas and if-then constraints, causal relationships and observable properties, is best taught experientially, but learning it hurts so, so bad. Music, especially electronic music, reliant as it is on abstraction and unrepentant as it is about hijacking your physiological responses to tempo and rhythm and dynamics, is a way to get there without going through it. Electronic music as practiced and developed by pioneers like Dick Hyman and Raymond Scott and Wendy Carlos is precise and intentional. In making his first electronic album, Younge took his cues from them, reminding a contemporary audience what a synthesizer, deep in its heart, really could be.

The lady of The Electronique Void, only ever seen through a man’s eyes, who’s being told what to do by him, sounds trapped by her history and by her position, her ancestors’ trauma echoing through her lineage and booming out of her as a phobia, distrust, misapprehension, rational response to a fucked up situation. Waterson’s text here seems to say that if his character could go back in time, catch her before the damage was done, she would be able to love. And that’s reasonable. Don’t get hooked. Don’t do wifey shit for a fuck boy. Don’t let it go to your head, no. It’s also possible he has no idea what he’s talking about. The lessons for men in The Electronique Void are unspoken but plain as day.

This music is an urgent tutorial. Adrian Younge looks at us and sees the frontline of a crisis, something we only have time to triage right now. This isn’t romantic and it isn’t about settling down. This is the fight of our lives: how to love.

This, too, is a story about control. It’s a manual, maybe half Rosetta Stone, half bird guide. It was made the way they made electronic music in the good old days, all analog everything, right after synthesizers shrunk to a manageable size and you didn’t have to trek down to a university to use one anymore. Hard-earned. Tastes different. Our parents’ electronic. And its subject is staying together, that thing we thought was their province. It’s about trying to fix what hurts. It’s about knowing better. Black Noise is men talking to men about women; Lemonade is a woman talking to women about men, and they both orbit around a failure we take for granted like the sun: loving you is complicated. It’s a skill; we forgot.

Adrian Younge calls The Electronique Void an academic album, by which he means it is both instructional and informational. There’s a problem at the heart of it, a woman who’s been told that she’s loved, but she doesn’t recognize that, can’t feel it, may have heard it all before, may be worrying about the wrong things. Jack Waterson, long a guitarist in Younge’s band, plays the role of narrator, sounding professorial and rather superior as he lays out for the woman where she’s erred. That vocoder you hear is Adrian, talking to her on a subterranean level, the way an artist must. There’s a strong sense of rules here, a prescription and a presumption that there is an agreed upon way to do it, and there is also a wrong way, or at least a way that won’t work. And the fact is, as didactic as that sounds, it might be the truth. Maybe everybody who’s alone can be cured. The discourse on the album is the kind of thing that happens when you go blonde and then you can’t keep ‘em off you. These truths are cold and hard, and our hero begrudges the well-meaning advice being rained down upon her as any independent woman would.

The science of love, its formulas and if-then constraints, causal relationships and observable properties, is best taught experientially, but learning it hurts so, so bad. Music, especially electronic music, reliant as it is on abstraction and unrepentant as it is about hijacking your physiological responses to tempo and rhythm and dynamics, is a way to get there without going through it. Electronic music as practiced and developed by pioneers like Dick Hyman and Raymond Scott and Wendy Carlos is precise and intentional. In making his first electronic album, Younge took his cues from them, reminding a contemporary audience what a synthesizer, deep in its heart, really could be.

The lady of The Electronique Void, only ever seen through a man’s eyes, who’s being told what to do by him, sounds trapped by her history and by her position, her ancestors’ trauma echoing through her lineage and booming out of her as a phobia, distrust, misapprehension, rational response to a fucked up situation. Waterson’s text here seems to say that if his character could go back in time, catch her before the damage was done, she would be able to love. And that’s reasonable. Don’t get hooked. Don’t do wifey shit for a fuck boy. Don’t let it go to your head, no. It’s also possible he has no idea what he’s talking about. The lessons for men in The Electronique Void are unspoken but plain as day.

This music is an urgent tutorial. Adrian Younge looks at us and sees the frontline of a crisis, something we only have time to triage right now. This isn’t romantic and it isn’t about settling down. This is the fight of our lives: how to love.

This, too, is a story about control. It’s a manual, maybe half Rosetta Stone, half bird guide. It was made the way they made electronic music in the good old days, all analog everything, right after synthesizers shrunk to a manageable size and you didn’t have to trek down to a university to use one anymore. Hard-earned. Tastes different. Our parents’ electronic. And its subject is staying together, that thing we thought was their province. It’s about trying to fix what hurts. It’s about knowing better. Black Noise is men talking to men about women; Lemonade is a woman talking to women about men, and they both orbit around a failure we take for granted like the sun: loving you is complicated. It’s a skill; we forgot.

Adrian Younge calls The Electronique Void an academic album, by which he means it is both instructional and informational. There’s a problem at the heart of it, a woman who’s been told that she’s loved, but she doesn’t recognize that, can’t feel it, may have heard it all before, may be worrying about the wrong things. Jack Waterson, long a guitarist in Younge’s band, plays the role of narrator, sounding professorial and rather superior as he lays out for the woman where she’s erred. That vocoder you hear is Adrian, talking to her on a subterranean level, the way an artist must. There’s a strong sense of rules here, a prescription and a presumption that there is an agreed upon way to do it, and there is also a wrong way, or at least a way that won’t work. And the fact is, as didactic as that sounds, it might be the truth. Maybe everybody who’s alone can be cured. The discourse on the album is the kind of thing that happens when you go blonde and then you can’t keep ‘em off you. These truths are cold and hard, and our hero begrudges the well-meaning advice being rained down upon her as any independent woman would.

The science of love, its formulas and if-then constraints, causal relationships and observable properties, is best taught experientially, but learning it hurts so, so bad. Music, especially electronic music, reliant as it is on abstraction and unrepentant as it is about hijacking your physiological responses to tempo and rhythm and dynamics, is a way to get there without going through it. Electronic music as practiced and developed by pioneers like Dick Hyman and Raymond Scott and Wendy Carlos is precise and intentional. In making his first electronic album, Younge took his cues from them, reminding a contemporary audience what a synthesizer, deep in its heart, really could be.

The lady of The Electronique Void, only ever seen through a man’s eyes, who’s being told what to do by him, sounds trapped by her history and by her position, her ancestors’ trauma echoing through her lineage and booming out of her as a phobia, distrust, misapprehension, rational response to a fucked up situation. Waterson’s text here seems to say that if his character could go back in time, catch her before the damage was done, she would be able to love. And that’s reasonable. Don’t get hooked. Don’t do wifey shit for a fuck boy. Don’t let it go to your head, no. It’s also possible he has no idea what he’s talking about. The lessons for men in The Electronique Void are unspoken but plain as day.

This music is an urgent tutorial. Adrian Younge looks at us and sees the frontline of a crisis, something we only have time to triage right now. This isn’t romantic and it isn’t about settling down. This is the fight of our lives: how to love.